East Boldre Airfield

(East Boldre Airfield can be explored during this walk around the site and also during this extended walk that also takes in Hatchet Pond and more).

As unlikely as it now may seem, the heathlands a little to the west of the village of East Boldre, south-west of Beaulieu, were once the site of an early airfield, initially used as the base for the New Forest Aviation School and then during the First World War as a pilot training ground. After the end of the war, flying ceased and buildings and equipment were progressively removed before, immediately following World War Two, the site was again relatively briefly used, this time for testing parachutes.

(1) East Boldre Airfield - the home of the New Forest Aviation School

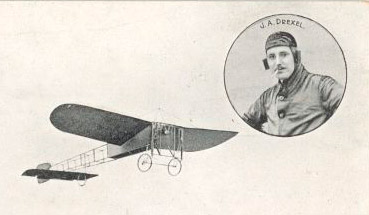

East Boldre Airfield, sited on Bagshot Moor, was one of Britain's first airfields. It started life as the home of the New Forest Aviation School, a very early aviation school which opened for business in May, 1910, not so many years after mans' first successful attempts to take to the skies in powered aircraft - the Wright Brothers claimed to have developed the first successful airplane only seven years earlier.

Image courtesy of hampshireairfields.co.uk

The enterprise was founded by two aviation pioneers, William McArdle, proprietor of an early motor business in Christchurch, and J. Armstrong Drexel, the son of an American millionaire. McArdle was the first of the pair to qualify as a pilot after learning to fly at the Pau Bleriot School in France, whilst Drexel failed to qualify in France but subsequently succeeded at East Boldre.

A strip of heathland at East Boldre was cleared for use as a rudimentary runway and three sheds, sited across the road from Bagshot Heath, were pressed into service, two as hangars and one as a workshop.

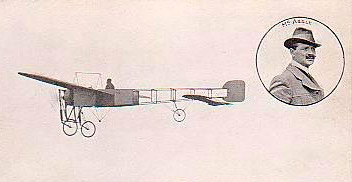

Image courtesy of hampshireairfields.co.uk

Lord Montagu was a supporter of the enterprise but formal permission to use the heathland as an airfield was not granted by the Office of Woods - the forerunner of the Forestry Commission - until late in 1910, some months after clearance work had actually been carried out.

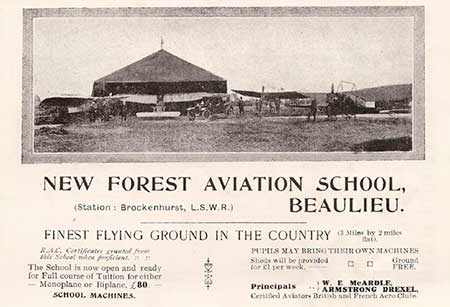

Up to ten bi-planes and mono-planes were used to teach would-be pilots the art of flying. Full courses of tuition were advertised at a cost of £80, which was, of course, a huge sum of money in those days. The airfield was promoted as 'the finest flying ground in the country - 3 miles by 2 miles flat' and pupils were invited, if they preferred, to bring their own machines.

Image courtesy of hampshireairfields.co.uk

Yet whilst credited with being the second flying school set up in Britain and the fifth worldwide, the venture was fairly short-lived and by early 1912 the school had closed and the aircraft were being sold off, although the old airfield and associated sheds remained in place.

(Maybe McArdle and Drexel were just a little ahead of their time and maybe, too, potential customers thirst for risk and adventure didn't quite match their own).

(2) Flying machines in the First World War - a bit of background

And so for a while, East Boldre Airfield lay largely idle, but it was destined soon to be used for First World War pilot training. But to what extent were aircraft used in warfare at that time?

Well, certainly at the beginning of the war, flying machines were very much a new technology with limited perceived military potential - indeed, powered flight was just eleven years old and the British air force comprised a mere thirty-three machines flying under the auspices of the Royal Flying Corps.

Aircraft such as the Royal Aircraft Factory B.E.2, a single-engine two-seat biplane, were used initially for reconnaissance and artillery observation behind enemy lines rather than for combat. Utilising large, unwieldy, primitive cameras, observers leant over the side of the aircraft to take photographs of the battlefields below to enable artillery fire to be more accurately directed at enemy targets.

Image courtesy of the Imperial War Museum - © IWM (Q 67698)

Air crews were initially unarmed although, as enemy aircraft were often engaged on similar missions, pilots would take along pistols and rifles to fire if the need arose. Grenades and small bombs also began to be carried in the cockpit and were dropped over the side of the aircraft onto the enemy below.

But as the importance of aerial observation grew, the need to take aggressive action against enemy aircraft became clear and so did a requirement to develop defensive capabilities. Specially adapted Lewis machine guns, mounted or fired from the shoulder, became the weapon of choice, initially used by the observer from the rear of the aircraft so as to avoid damaging the whirling propeller blades.

By 1915, however, forward facing machine guns were being fitted onto aircraft, eventually cleverly synchronised to shoot through the propeller blades without causing damage. And by 1916 and 1917, fewer lone fighters cruised the skies and instead larger formations of aircraft flew together, with individuals breaking away to engage in 'dog fights'.

New aircraft were introduced into service, aircraft such as the Royal Aircraft Factory S.E.5 (from March 1917) and the later improved S.E.5a, fast, nimble single seater fighters that, although still wooden framed and fabric covered, have since been described as the 'Spitfires of World War One'.

Image courtesy of the Imperial War Museum

Reflecting air power's increasing importance to the war effort, on 1st April, 1918 the Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Naval Air Service were amalgamated to form the Royal Air Force. Fighters by then were being used at low levels to support ground troops, whilst specialist bombers had been developed that could fly for up to eight hours at a top speed of ninety-seven miles per hour (156 km per hour) while carrying one ton of bombs - the bombers, of course, were not very manoeuvrable and needed protection from accompanying fighter aircraft.

So, during a little over four short years, the use of aircraft had evolved from flying simple but extremely dangerous reconnaissance missions to being important weapons of war with a hugely significant military role.

(3) East Boldre Airfield and the First World War

East Boldre Airfield was first considered during late 1913 as a site for a Royal Flying Corps 'station', some months before the outbreak of the First World War, but its use was initially rejected as the characteristics of the surrounding open Forest were considered to constitute a hazard to trainee pilots who might have to make unplanned landings. (The Royal Flying Corps was the air arm of the British Army and a predecessor of the Royal Air Force).

And in any case, demand for training sites at this time was relatively limited although the military did take up a local presence as one of the New Forest School of Aviation's sheds was taken for use by the War Department in 1914 on a three year lease.

By 1915, however, as the military use of flying machines increased, the demand for pilots to fly on the Western Front also inevitably increased. The merits of East Boldre as a base for flying training were consequently reviewed and the airfield was eventually designated as the site of a new Royal Flying Corps camp officially known as RFC Beaulieu.

Image courtesy of the Imperial War Museum - © IWM (Q 66016)

There, pilots, observers and ground crew were trained prior to deployment elsewhere - depending upon their roles, trainees were expected to display competence in taking off, landing, cross-country flying and navigation; and to also undertake bombing and machine gun practice - Hatchet Pond and the Solent near to Pitts Deep were both conveniently nearby locations for target practice.

A lease was agreed with New Forest officials, compensation for loss of grazing land was negotiated, gorse and other bushes were removed and the ground was levelled and drained before, in mid-December, 1915, the first aircraft arrived.

Early in 1916, work started on the Training Station section of the camp, located close to the houses of East Boldre. Accommodation huts were to be provided along with three iron-framed hangars and other infrastructure items including the building that survives to this day as East Boldre Village Hall, but which originally served as both the Officers' Mess and a YMCA facility.

Image courtesy of hampshireairfields.co.uk

Increasing use of the airfield for training purposes necessitated further construction in 1918, remarkably close to the end of the war, including the development of what was known as the Squadron Site, alongside and primarily to the south-east of the Beaulieu to Lymington road.

Four large 'truss' hangars, built as two doubles, were located there along with a power house, workshops and other facilities. The men's living quarters were adjacent and the officers' quarters a little further away to the south-west. Living quarters for members of the Women's Royal Air Force (WRAF) were also nearby, situated a little to the north-west of the Beaulieu to Lymington road, and so were a Small Arms Firing Range and Officers' Squash Courts.

(4) First World War flying - a risky business

Flying at this time was a particularly hazardous occupation using often unproven aircraft that, particularly initially, were of flimsy, mainly wooden and linen or canvas construction strengthened with wire struts.

Image courtesy of the Imperial War Museum - © IWM (Art.IWM ART 3071)

Furthermore, the technology was in its infancy, engines were not wholly reliable, navigation aids were limited and training was often inadequate. And safety equipment was virtually non-existent - to encourage pilots of damaged aircraft to attempt to return home, even parachutes were not made available.

Accidents and fatalities as a result of enemy action were commonplace and it has been said that on average, a combat pilot had a life expectancy of no more than a few weeks - the life expectancy of a new pilot in 1917 was apparently an unimaginably low eleven days.

Some pilots even took a revolver into the air with them, not just to shoot at enemy aircraft but more to end their own lives in the event of their plane catching fire - being burnt alive was a fate few could face without fear.

Image courtesy of the Imperial War Museum)

In total, fourteen thousand Allied pilots perished during the First World War and, almost unbelievably, over half of those fatalities - 8,000+ - occurred during training. Many of the aircrew, perhaps the majority, were under twenty years of age!

In fact, well-illustrating the precarious nature of flight in those early days, thirty-three airmen and flying instructors were killed in flying accidents at East Boldre alone - nineteen of these personnel are buried in the churchyard at St. Pauls Church, East Boldre.

The BBC Timewatch documentary below contains lots of information about flying during the First World War together with contemporary film and photographs. It is well worth watching to help place pilot training at East Boldre into a wider context.

(5) East Boldre Airfield after the war

Flying training continued for a little while after the end of the First World War - well into 1919 - by which time, on 1st April, 1918, the Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Naval Air Service had been amalgamated to form the Royal Air Force whereupon RFC Beaulieu had become No. 29 Training Depot Squadron, RAF.

By the end of 1920, however, much of the airfield equipment had been removed and the site was eventually returned to open Forest, presumably to the relief of the Verderers and, in particular, the local commoners who were presumably anxious to reclaim valuable grazing land.

All then remained quiet and peaceful at the old airfield until the early days of the Second World War when, in 1940, at the height of fears of a German invasion, anti-invasion poles were put in place to thwart potential glider landing attempts - the poles were removed late in 1944, after invasion fears eased.

But, of course, a large Second World War airfield - Beaulieu Airfield - was constructed nearby on the other side of the Lymington to Beaulieu road. But this did not use any of the site of the old airfield, which was considered to be too small to accommodate the new, much larger airfield.

The old site was, however, used from 1945 to 1950 by the Airborne Forces Experimental Establishment, which was then based at the adjacent Second World War airfield, as a parachute testing dropping zone. Dummy drops, live descents, container and pannier drops were undertaken, but drops of heavier items such as guns and jeeps were usually done onto the main airfield.

(6) Reminders of the old airfield

Nothing of the old airfield now remains standing, apart from the brick-built, white-washed YMCA and Officers' Mess building that is still in use as East Boldre Village Hall.

However, mysterious lumps of concrete, strips of concrete that mark building outlines, steel edgings of old roads and concrete bases lie part-concealed in the turf or hidden from view under gorse bushes.

Explore the site of the Training Station where opposite the village post office and shop can be found the foundations of one of three metal hangars and foundations of other buildings, too.

Then within the Squadron Site look out for relics that include hangar and other building foundations, raised supports for the power house's fuel tank, concrete bases on which stood engines and generators, and two unexplained structures that it has been suggested might have housed a blacksmith's furnace or stove.

And then across the road from the Squadron Site is an earthen, bracken and bramble covered, quite prominent linear mound marking the site of the Small Arms Firing Range - presumably the mound was the firing range butt, the backcloth to the targets that prevented stray bullets reaching the Squadron Site.

Beside the Lymington to Beaulieu road can still be seen the feint outline of the guard house, whilst farther along, almost opposite the entrance to the Hatchet Moor car park are huge white letters laid out on the ground, spelling the word BEAULIEU. Each letter is around 4.5 metres (15 feet) high and the whole word spans around 33.5 metres (110 feet). Their origin is something of a mystery but it has been assumed that they were put in place in the days of the flying school.

(7) More reminders of the old airfield

(8) Yet more reminders of the old airfield

References:

They Flew from the Forest: Alan Brown

Discover East Boldre Airfield 1910 - 1920: East Boldre Village Hall

The Imperial War Museum

Royal Aircraft Factory B.E.2

Royal Aircraft Factory S.E.5

BBC Timewatch - WW1 Aces Falling

Quick links

More links

Other related links

Search this site