White Moor - its military history

In the New Forest, the First World War ushered in an era of intensive military activity as wide open spaces, common land, varied terrain and a relatively sparse local population attracted both the army and the nation's fledgling air force.

(Military manoeuvres had already taken place in the New Forest during the late-Victorian period, and a number of Victorian rifle ranges had also been created, including one on White Moor).

First World War camps and the 7th Division

At White Moor, a short distance to the east of Lyndhurst, soldiers camped before embarking for the fronts, leaving behind, deep amongst the heather, the remains of trenches used for warfare practice, simulating the unenviable mud and squalor that soon would be faced in action.

In early to mid-September, 1914, not long after the start of the war in late July of that year, nine battalions were gathered together on White Moor and nearby on Lyndhurst's old Race Course, to form the 7th Division. Indeed, the west window of the Catholic Church in Lyndhurst commemorates some of these men, soldiers of the 'Immortal 7th Division'. In October, 1914, 15,000 sailed from Southampton for France, heading for the battlefields of Ypres. Three weeks after going into action, only 2,380 were still alive.

Miss Dorothy Cavill, a local resident who was about 6 years old at the time, remembered the 7th Division leaving Lyndhurst, noting: 'When they left, we lined the roads and gave them a very hearty goodbye. Sadly, they were all wiped out'.

Similarly, Miss Cavill separately recalls volunteers leaving Lyndhurst: 'It was a very sad day when the volunteers left for the First World War. We lined the side of the road and my mother sat me on the field gate, now the Enchanted Tearooms (the Enchanted Tearooms were to become a popular Italian restaurant). There were lots of hugs and kisses and tearful farewells and I doubt if many of those men came back'.

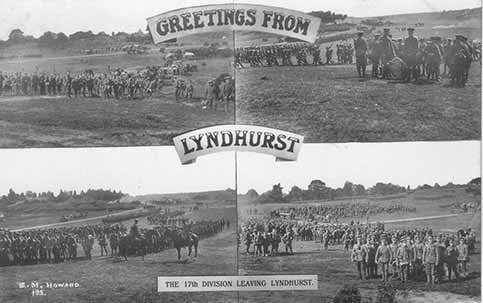

The contemporary postcard shown here, captioned 'Greetings from Lyndhurst', purports to show the '17th Division leaving Lyndhurst', but surely it is the 7th Division. The card's relatively light-hearted nature perhaps illustrates the extent to which many thought that the war would not last very long, but they could hardly have imagined the horrors that soon would be unleashed. (This unposted card was published by E.M. Howard - Kelly's 1911 Directory includes a Lyndhurst entry for Mrs. Edith Mary Howard, Stationer, presumably the same E.M. Howard).

The two photographs jointly captioned 'Soldiers from the camp on White Moor' recall those days. The first is from a contemporary postcard written by '1756 Private William White', who gave his address as 3 / 4 Hants Regiment Cookhouse, Lyndhurst Road Camp, Lyndhurst. The other picture is from the same source and presumably shows men of the cookhouse relaxing in what was probably a short-lived break.

Commonwealth troops also joined the war effort, and were billeted in the New Forest. Miss Cavill remembers meal times on White Moor:

'At one time there was a regiment of Indians stationed in the camp, I think they were Sikhs. I and my brother would go into the camp and watch them make their chapattis on the ground. My brother….made sure my shadow didn't fall across the chapattis when they were cooking them, if so they said they would put their knife through us so we made sure we were on the right side of the sun. They gave us a chapatti and we hung it on the wall as a souvenir.'

The Grenade School and Trench Mortar School - the Southern Command Bombing School

Towards the end of 1915, construction of a Grenade School located on White Moor was commenced. Completed in March, 1915, and taking up around 190 acres, soldiers from across the Empire passed through the school where they were instructed in the destructive arts of grenade warfare, learning about grenade use, particularly in the context of attacking and clearing trench systems.

Shortly after, in 1917, a Trench Mortar School opened on adjacent land to the north-west of Matley Wood, this occupying a further 230 acres. (A mortar is a short tube designed to fire a projectile at a steep angle so that it falls straight down on the enemy. The mortar was ideally suited for trench warfare, hence the use of the term 'trench mortar').

Local resident Charles Hall leaves a vivid description from 1916:

'The War was at its height and beyond this hill (Bolton's Bench) in the distance was a bombing range where troops were trained in hand grenades (Mills bombs as they were called then) and land mines. No one was allowed beyond this hill, and there was an almost continuous sound of explosions and bangs coming from the range'.

Almost inevitably, accidents happened. Here is Miss Cavill, again: 'There were several regiments camped there, and there were many tragedies of men being blown up, and on several occasions they had military funerals with the coffin on the gun carriage draped with the Union Jack and the band marching behind playing 'The Dead March from Saul'. Again many villagers lined the cemetery road, it was all very sad. I can remember it so well ………'.

An old photograph of the Bombing School 'Class of 1916' shows seated in the front row, the son of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, who lived at nearby Minstead and is buried there in the churchyard.

War Dog Training School - White Moor / Matley Ridge

War Horses in recent years have quite rightly received belated recognition for their contribution to the First World War, war effort; for after all, an estimated eight million horses and countless mules and donkeys were killed in action.

But what of War Dogs? Perhaps surprisingly in these days of instant communications with friends and relatives on the opposite side of the world, dogs also played a part as messengers in the First World War. Trained to carry messages under battle conditions, the dogs were from a variety of breeds including Airedale Terriers, Border Collies, Lurchers, English Sheepdogs, Retrievers and mongrels. As crude as it now seems, messages were placed in tins tied around the dogs' necks - the dogs could run messages from the trenches back to command in a quarter of the time that a man could, and were far less likely to be hit along the way.

But the dogs were not just used as a means of transporting communications - the Red Cross used them to find wounded soldiers, whilst dogs were also used for tracking the enemy, detecting explosives and warning of imminent attack.

And of course, the dogs needed training before deployment. The British War Dog School was established in 1917 - somewhat late in the war when it's considered that the Germans had several thousand dogs in use from the start of the hostilities. Shoeburyness, in Essex, was chosen as the location for the training school as the guns of the Western Front could be heard across the North Sea. Hundreds of dogs were trained there, sourced from rescue centres such as Battersea, before the demand grew to such an extent that public appeals were made for people to donate their pets.

In 1918, however, the Shoeburyness site was moved to White Moor / Matley Ridge, to the site of the then recently closed Trench Mortar School, where around 200 dogs were trained before the school was moved to Bulford, Wiltshire, in May 1919.

Sadly, it has been estimated that around one million dogs were killed in action.

Evidence of war

Lumps, bumps and mysterious hollows; over-grown trenches and water-filled craters all hint at past use of this now beautiful area of lowland heath, but more tangible evidence of First World War land usage occasionally comes to the surface.

The exact identity of the war-time explosive shown in the accompanying photograph is unknown, at least to this writer, who stumbled across it - not literally - quite a few years ago near Decoy Pond Farm, a short distance to the east of Matley Ridge. Its presence was reported to the Forestry Commission and a bomb disposal expert was called to make it safe.

And then not very many years ago, during the construction of a new house in the garden of an older property adjacent to White Moor, an unexploded grenade was discovered. After being placed in a blast-proof box, this was taken onto White Moor and destroyed.

But somewhat reassuringly, in recent years part of White Moor and the surrounding heathland has been methodically searched and cleared by the authorities, but walkers and others are advised to take care, and if a grenade or whatever else is 'stumbled across', give it a wide berth and advise Forestry Commission staff of the find.

Find out more about White Moor

and about how East Boldre Airfield was used for First World War flying training

References:

Lyndhurst Historical Society publications: Roy Jackman

A Hampshire Album, 1900-1940: Anthony Brode

Recollections of Miss Dorothy Cavill and Charles Hall, courtesy of the Christopher Tower New Forest Reference Library

New Forest Knowledge - Southern Command School of Bombing

The Role Of Dogs In WW1 Trenches - Dogs in World War One

Shoeburyness, Essex: British War Dogs

New Forest Knowledge - War Dog Training School - Matley Woods, Lyndhurst

More links

Other related links

Search this site

Sadly, 58 animals were killed - 35 ponies, 13 cows, 8 donkeys and 2 sheep, whilst a further 32 were injured - 3 pigs, 9 donkeys, 11 cows and 9 ponies.

(Forty-three accidents occurred in daylight, 15 at twilight and 101 in the dark. Twenty-seven accidents were not reported by the driver involved).

Here's just one horrific example - Three donkeys killed in collision with van at notorious New Forest blackspot (Advertiser and Times)