Castle Hill, Ringwork and Bailey Castle

(Castle Hill, Ringwork and Bailey Castle can be explored during this fairly short, 2¾ mile New Forest walk).

Castle Hill, Ringwork and Bailey Castle is located close to the parish boundary separating Woodgreen from Godshill. The castle is actually on the Woodgreen side of the parish boundary, although it is often described as being in Godshill.

Overlooking the Avon valley on the north-western edge of the New Forest, Castle Hill provides spectacular views over the river and on to the chalk-lands beyond. An adjacent minor road runs along this hilltop ridge, beside Godshill Wood, and provides access to a number of popular viewpoints.

(The castle can be found at Ordnance Survey map reference SU167162 - shown with an 'X' on the location map).

(1) A bit of background

In the violent times following the Norman Conquest of 1066, there was a need for relatively quick and easy to construct, secure temporary (and sometimes not-so-temporary) encampments to serve as a base from which attacks could be launched and captured land defended.

Motte and Bailey castles and similar Ringwork and Bailey castles evolved to meet this need and in some cases further developed as defended aristocratic or manorial settlements.

Motte and Bailey castles

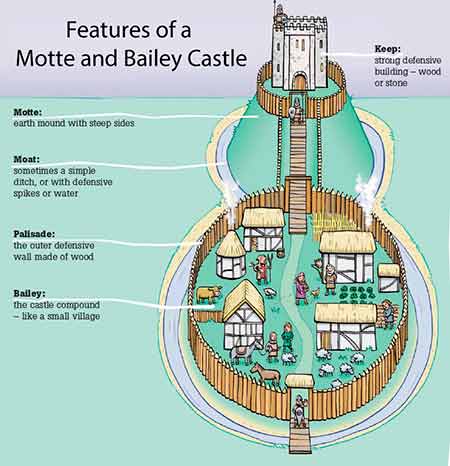

Motte and Bailey castles were built across northern Europe from the 10th century onwards, spreading from Normandy into England following the Norman invasion. They comprised a strong wooden, or sometimes stone, structure known as a Keep - occupied by the military force's senior figures - built onto a raised Motte, an often steep-sided, frequently artificial, conically shaped earthen mound. An encircling wooden palisade was often added to increase security.

(Image courtesy of Marlborough Science Academy)

The Bailey was an adjacent embanked, often fenced enclosure within which were located living quarters for the troops, storage space for military equipment and foodstuffs, resting places for horses and other livestock, and space for the further necessities associated with early post-Conquest warfare. The Bailey was usually on level ground and was also often protected by a wooden palisade, and external ditch.

A moat, too, was sometimes present around the whole complex, providing an additional layer of protection for those within.

Ringwork and Bailey castles

At Castle Hill, the fortification was a Ringwork and Bailey castle, a type that appeared in England a little prior to the Norman Conquest and continued to be built during the late-11th and 12th centuries. Castles of this type were characterised by the absence of a motte - the keep, if indeed there was one, was sited within a usually oval or circular-shaped ringwork, sometimes referred to as an Inner Bailey. This area was enclosed by an earthen rampart sometimes topped by a timber palisade, and protected by a substantial ditch.

(According to Historic England, ringworks are rare nationally with only 200 recorded examples. Less than 60 have baileys).

(2) Castle Hill, Ringwork and Bailey Castle

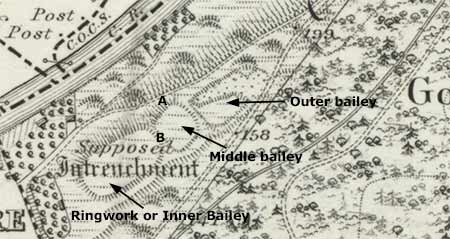

(The earthworks appear much the same on modern maps, but reflecting the uncertainty associated with the site, the Victorian map makers added the notation 'Supposed Intrenchment' - an 'entrenched fortification, a position protected by trenches').

Heywood Sumner in 'A Guide to the New Forest', written in 1923/24, called the fortifications on Castle Hill 'earthworks that appear to belong to the Norman period'. They were described as a 'ring-work and bailey' castle by Nicola Smith (Hampshire Studies, 1999), and are referred to by Historic England as an 'oval ring motte with a smaller outer bailey ... and a possible further bailey'.

Chris Read (Hillforts of the New Forest National Park, published in 2018), perhaps more accurately states that the earthworks are the remains of a 'ringwork castle with two outer baileys'.They are shown on modern Ordnance Survey maps simply as 'Ring and Bailey'.

To the untrained eye, and maybe also to many trained eyes, the remains don't look hugely impressive, particularly as much of the site is within mature woodland with a fairly dense under-storey of bracken, brambles and other vegetation. Patient examination will, however, reveal much of the layout of this long-lost citadel that back in the day, before the trees took hold, would have provided far-reaching views to the north and west sufficient to reveal the approach of aggressors.

The castle is aligned on a south-westerly / north-easterly axis. The earthen banks and ditches associated with the oval ringwork, or inner bailey, are at the south-western end and there is an adjacent smaller, square middle bailey immediately to the north-east, separated from the ringwork by a still fairly pronounced ditch which, no doubt, provided the material for the adjacent banks. The presumed outer bailey, slightly larger than the middle bailey but much damaged by 19th century, or earlier, gravel extraction, follows in line.

A quite wide terrace, presumably the source of the earth for the adjacent banks, runs almost the full length of the site, on the north-westerly, Avon valley side.

(3) Outworks

Around 300 metres farther to the north-east, intersected by the minor road running alongside Godshill Wood, is what is presumed to be an outer defensive work that obstructed access to the castle. This earthwork runs across the ridge and comprises a very obvious earthen bank 26 metres (85 feet), or so, long; 12 metres (39 feet) wide; and up to 1.4 metres (4½ feet) in height, with evidence of a ditch on the outer side.

(The age of this bank and ditch is uncertain - some consider it to be of Iron Age origin, rather than Norman, although there is no agreement on this).

Two further defensive banks and ditches have also been recorded: one, still impressively visible, runs down to the river from the north-western edge of the outer bailey; the other, recently detected by Lidar mapping, runs in the same direction from the north-western edge of the inner bailey. Both presumably protected the castle from approach from the direction of the river.

(4) Interpretation of the remains

Interpretation of the castle remains is fraught with difficulty as this is a complex site that reflects occupation and changes of use over many centuries. It has been suggested, for example, that the ringwork section of the castle, at least, overlies an earlier, probably small, Iron Age hillfort - two banks, for instance, both possibly of Iron Age origin, can still be seen running alongside the ringwork's third, inner bank, which apparently may also be of Iron Age origin.

The Romans, too, are said to probably have been active here, and the Norman castle may not have been completed or was in part subsequently destroyed.

Add to that the possibility that the site was later used as the location for a Forest lodge, and that gravel extraction subsequently destroyed part of the earthworks, and it is easy imagine the difficulties of sorting out exactly what relates to which era.

The works have, however, been interpreted as the possible remains of an adulterine castle, that is, a fortification built during the 12th century without royal approval, during the civil war, known as the Anarchy (1135 and 1153), that raged after the death of Henry I. Then, Stephen of Blois seized the throne with the help of his brother, Henry of Blois, Bishop of Winchester.

It is further suggested that the remains relate to a siege castle, a probably hastily erected, temporary fortification without any masonry structures, built in 1148 by Hugh de Puiset - nephew and supporter of Stephen and Henry, and from 1153, Bishop of Durham - during the siege of nearby Downton.

Assuming this to be correct, the Castle Hill fortifications have strong links to Downton Moot, the site of a motte and bailey castle a mere 6 kilometres (not quite 4 miles) away. Built by Henry of Blois in 1138, in the midst of the civil war, the castle at Downton was located so as to control the nearby crossing of the River Avon. However, the Earl of Salisbury, a supporter of the opposing side in the civil war, captured the castle by stealth in 1147 and held it until starved out by the siege.

But in reality, the origins of the Castle Hill fortifications remain at least a little uncertain, although it's quite a thought that here, overlooking the splendours of the Avon valley, a medieval army for a short space of time lived within the area surrounded by the banks and ditches we see today.

References:

Proceedings of the Hampshire Field Club & Archaeological Society, Volume 54 – The Earthwork Remains of Enclosure in the New Forest: Nicola Smith

A Guide to the New Forest: Heywood Sumner

Norman Castles in Britain: D.F. Renn

Hillforts of the New Forest National Park: Chris Read (New Forest History and Archaeology Group)

Wikipedia - various pages

Historic England - Castle Hill

Historic England - Downton Moot

Downton Moot

Quick links

More links

Search this site