Lymington Salterns

A brief history

The Lymington Salterns spanned the coastal marshes right the way from Lymington to Hurst Spit and formed part of an important industry that flourished from the medieval period through to the early 19th century.

Salt extracted from seawater was then a highly valued commodity used for culinary purposes, as part of the tanning process and, perhaps most significantly, to preserve meat, fish and vegetables by reducing the potential for invasion by bacteria, fungi and other nasties.

Indeed, it has been said that much of Lymington's 17th and 18th century prosperity was based on revenue generated from the salterns in the Keyhaven and Pennington Marshes - Daniel Defoe in the 18th century records 'that all of Southern England obtained its salt from Lymington'.

(1) The extraction of salt from seawater

An early, somewhat laborious method involved washing the salt from sand and silt in a not particularly efficient process that involved filling a trench with turfs, straw or reeds; putting in the trench sand or silt that had become impregnated with salt; and then running water through it.

The turfs, straw or reeds acted as a filter that retained the sand or silt, whilst the salty water - the brine - passed through ready for further processing and collection. The waste sand or silt was typically then discarded on a mound of ever increasing size.

In the Lymington Salterns, however, from at least the early 17th century, seawater was often diverted along narrow, usually purpose built, clay-based tidal trenches; and then fed into shallow pans that varied in size from 25 to 120 square yards and were bordered by low earthen banks and 'secured at the bottom with clay and gravel' or were made from lead or iron.

Wind and sun caused at least some of the water to evaporate, leaving behind a concentrated solution of brine.

In climates where sunshine was consistently available, the brine would be left to further evaporate before the salt could be taken, but here the weather cannot be relied upon and, of course, a spell of rainfall can nullify the effects of days of evaporation, so the process was helped along by boiling the salt-laden water - the brine - after an initial period of natural evaporation.

(2) Celia Fiennes - a late 17th century account of salt making

Celia Fiennes travelled around England on horseback between 1684 and about 1703, and recorded details of her journeys. She visited Lymington and provided a fascinating, if lengthy, account of how the Lymington Salterns operated:

'... Limington, a Seaport town, it has some few small shipps belongs to it and some little trade but the greatest trade is by their salterns; the Sea water they draw into the trenches and so into severall ponds that are secured in the bottom to retain it and it stands for the sun to exhale the watry fresh part of it, and if it prove a drye summer they make the best and most Salt for the rain spoyles the ponds by weakening the Salt; when they think its fit to boyle they draw off the water from the ponds by pipes which conveys it into a house full of large square iron and copper panns, they are shallow but they are a yard or two if not more square, these are fixed in rowes one by another, it may be twenty on one side, in a house under which is the furnace that burns fiercely to keepe these pans boyling apace, and as it candy's about the edges or bottom so they shovel it up and fill it in great Baskets, and so the thinner part runns through on Moulds they set to catch it which they call Salt Cakes; the rest in the Baskets drye and is very good Salt, and as fast as they shovel out the boyling Salt out of the pans they do replenish it with more of their Salt water in their pipes; they told me when the season was drye and so the Salt water in its prime they could make 60 quarters of Salt in one of those pans which they constantly attend night and day all the while the fire is in the furnace, because it would burn to waste and spoyle the pans, which by their constant use wants often to be repaired; they leave off Satterday night and let out the fire and so begin and kindle their fire Monday morning, it's a pretty charge to light the fire; their season for making Salt is not above 4 or 5 months in the year and that only in a dry Summer; these houses have above 20, some 30, others more of these panns in them, they are made of Copper; they are very carefull to keep their ponds well secured and mended by good Clay and Gravell in the bottom and sides, and so by sluices they fill them out of the sea at high tides and so conveyed from pond to pond till fit to boyle'.

(It was in the early 17th century that 'floor pans' became a compulsory feature of the salterns as a result of orders to replace sand mounds with floor pans (and lead with iron). Almost needless to say, some saltern owners were resistant to making the necessary structural alterations, particularly during the summer boiling season, albeit ultimately to little or no avail. Relatively large scale land reclamation was a consequence of the introduction of these new processes).

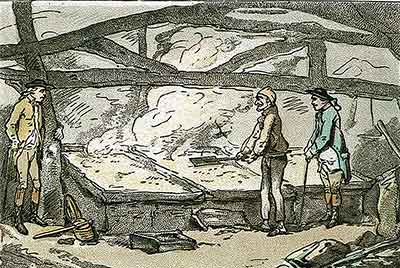

(3) Thomas Rowlandson's visit to the salterns

A 1784 drawing by Thomas Rowlandson depicts windmills and a series of square floor pans bounded by low banks close to the site of 'Mrs Beeston's baths' - later the salt water baths - in Lymington.

Another Rowlandson drawing - shown here - depicts what was described as the 'Inside of a Saltern at Lymington.....'.

(4) Mr. Charles St. Barbe - the early 19th century

Mr. Charles St. Barbe, the principle owner of the Lymington Salterns in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, provided an account of the processes in use at that time for inclusion in Charles Vancouver's View of the Agriculture of Hampshire (1813):

'The sea water is first admitted into feeding ponds, from whence it flows into levels, in which there are partitions, forming pans, as they are called, from 20 to 30 square perches each: these receive the sea water from the feeding ponds to the depth of about 3 inches, and from which it passes from the higher to the lower pans, exposed to the action of the sun and wind, until the brine becomes of sufficient strength to be pumped up by small wind engines into a cistern, whence it is conveyed by troughs into the respective iron pans for boiling'.

Other contemporary 19th century descriptions varied slightly, suggesting that saltern owners had their own favoured methods of working or that processes evolved over time, but the principle was always broadly the same.

Mr. St. Barbe also noted that: 'the average annual period of working the pans is 16 weeks, during which time each pan yields from 16-17draughts or boilings weekly, amounting to 3 - 3¼ tons of merchantable salt per pan, for every 6 days they continue to work'. But illustrating the works dependence upon the weather, in 1802 boiling was largely limited to a meagre 2 weeks 'in consequence of almost constant rains'.

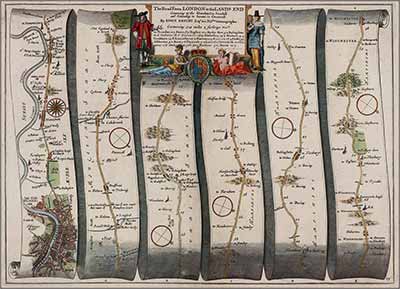

(5) Transportation

Salt was shipped out using canals that can sometimes still be seen today, such as at Moses Dock, near Woodside; Maiden Dock, beside Eight Acre Pond; and Pennington Dock - all are shown on the Keyhaven and Pennington Marshes walk map. Coal to fuel the boiler houses came in along the same routes in barges that on their outward journeys would take away the salt to larger ships docked, for example, in Lymington and Southampton, which would transport the cargo farther afield.

Salt destined for the local inland market was transported using donkeys or packhorses along routes such as the Salt Way, which is shown on late 18th century maps of the New Forest.

(6) The rise and fall of a once prosperous industry

Recent research - details published in 2009 by the Hampshire Field Club and Archaeological Society - suggests that for Iron Age people settled in the area, 'salt making was a significant component of their possibly seasonal economic base'.

The Domesday Book, compiled shortly after the Norman invasion in 1066, meanwhile, records 6 salt pans in Hordle parish, which at that time extended to include Hurst Spit, but noted none elsewhere in the area. The earliest reference to salt making at Lymington, however, was in 1132 when a tithe of Lymington salt was granted to Quarr Abbey on the Isle of Wight, although it may well be that the industry locally was already well established by that date.

In 1625 there were 5 'salt-works' at Milford and Keyhaven, 13 at Pennington, 8 at Woodside, 3 at Oxey and 2 'in the Rows'; whilst production seems to have peaked in the mid-18th century when there were 163 pans in the Lymington area. Indeed, analysis completed by a past vicar of Pennington showed that in 19 of the years between 1724 and 1766 - the years for which records exist - 4,612 tons of salt from the Lymington area were exported through Southampton in 64 ships, 12 of which were destined for Newfoundland, 33 were bound for America, 5 for Ireland, 7 for Norway and 4 for the Channel Islands.

Sadly, the story thereafter was one of steady decline in the face of seemingly ever increasing duty to be paid on the finished product (the tax was at its highest after 1805); the high costs associated with the purchase and transport of coal to fuel the boiling processes; the payment of yet more tax on the coal; and competition from abroad and from inland salt producers, such as those based in Cheshire.

Never-the-less, in the years 1801, 1802 and 1803, average annual production of about 4,000 tons was still noted; although by 1813 there were only '68 pans in the Pennington and Lymington saltings' and by 1836 only 14 salterns remained in operation. The last closed in the mid-1860s.

From the early 19th century, or maybe from a few years before then, equipment and buildings were being removed, ponds filled in, drainage schemes implemented and much of the ground flattened, cleared and turned over to grazing land, converted into oyster beds or used for other purposes.

The 1868 Ordnance Survey map, for example, shows Oyster Beds at Woodside, a little north of Moses Dock, where now there are lagoons and marshland; and nearby, two Pumping Mills, whilst by 1895-97, a golf course is shown in Oxey Marsh, a little south of Moses Dock, and Saltings - presumably generic, historic or disused sites - are marked in Keyhaven and Pennington Marshes.

But elsewhere around the world, however, in places where there is limited access to rock salt, refrigeration facilities and other modern technologies, or where traditional methods are simply preferred, the use of sea salt in food preservation continues to this day.

(7) Reminders of the past

Maiden Dock, Moses Dock and Pennington Dock, with their accompanying water channels used to bring in coal and take out salt, can still be seen today; whilst two brick-built salt industry buildings near Moses Dock have also stood the test of time, although both are somewhat crooked in appearance.

Probably dating from the 18th century, they have been described as boiling houses, although the smaller of the two may have been used for storage. (Archaeological surveys in 2010 revealed evidence nearby of another structure, formerly used for coal storage, and a further building on the site).

The metal pans, wind pumps and boiler houses have long since disappeared, although old, low earthen banks can still be seen - some noticeably arranged in grid patterns, surrounding waterlogged square or rectangular patches of ground.

Still visible, too, are ditches, pits and occasional badly eroded mounds upon which boiling houses and wind pumps once stood, spread across the marshes as fading reminders of this once flourishing trade.

The Chequers Inn, a picturesque 16th Century pub located at Woodside, also provides a tangible link with the past for it is reputed to have been the old headquarters of the Salt Duty Collectors.

Homes for wildlife

Much of the land on which the old salterns stood has not been subject to intensive agriculture, although some has been lost to mineral extraction, landfill and later grassland landscaping. What remains provides valuable habitats for a wide range of primarily wetland wildlife.

References:

The Salterns of the Lymington Area: Arthur T. Lloyd

The Illustrated Journeys of Celia Fiennes 1685-c.1712: Edited by Christopher Morris

The changing technology of post medieval sea salt production in England: Jeremy Greenwood

Hants Field Club

Quick links

More links

Search this site